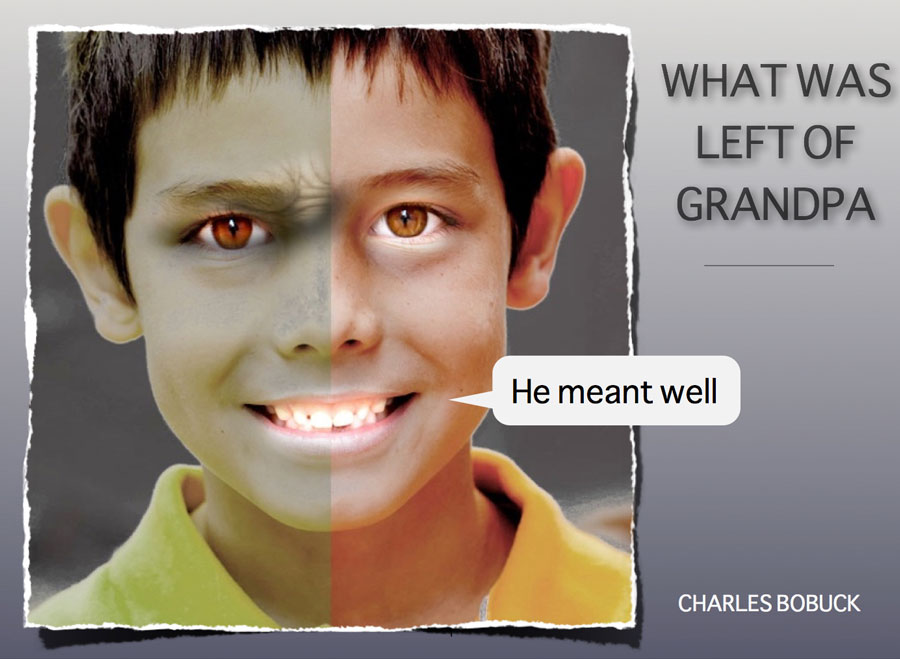

GRANDPA CHARLES

A very long time ago, Aristotle got in an argument with Plato about chickens and eggs. Which came first. That kind of thing.

Neither paused to consider roosters. Roosters and the vast majority of male animals have always been regarded primarily as accessories to the process of the continuation of the species. I have no problem with that. Women producing daughters with the ultimate purpose of those daughters making more daughters seems like a sensible system which allows for a beautiful tradition of photographs with four or five generations of mothers and daughters.

Men were not overlooked. It’s just that nature never intended them to be in the photos to start with. Especially affected were the older men, the grandfathers, the great-grandfathers. They tended to become primarily decorative additions to overstuffed chairs.

This was true for my grandfather. And in time, so it will be with me.

When my mom was young, my grandfather provided for her and the rest of the family in the manner that was expected of men during the Great Depression. He had his personal interests; his work, music, reading, smoking cigars, but satisfaction came from providing for the family. Once mother married, replacing him with a husband, his center became blurred. She was the final chick leaving the coop and he suddenly found himself with little distraction other than a wife he had not noticed in many years.

While my mother was the last to leave home, she was not the youngest child. She had a younger brother, Tommy, who had suffered a difficult birth. I don’t know what went wrong, medicine was not very sophisticated in small towns in Arkansas a hundred years ago. The younger uncle had the mind of a child. He was kept at home, never going to school, church, or anywhere that might cause embarrassment or require explanations. When I was young and visited the grandparents, Tommy and I played together, we both loved to draw. While I would copy characters from comic books, he mainly copied cigarette advertisements from magazines. He liked to draw women smoking. I thought he was a terrible artist back then. I might have a different opinion now.

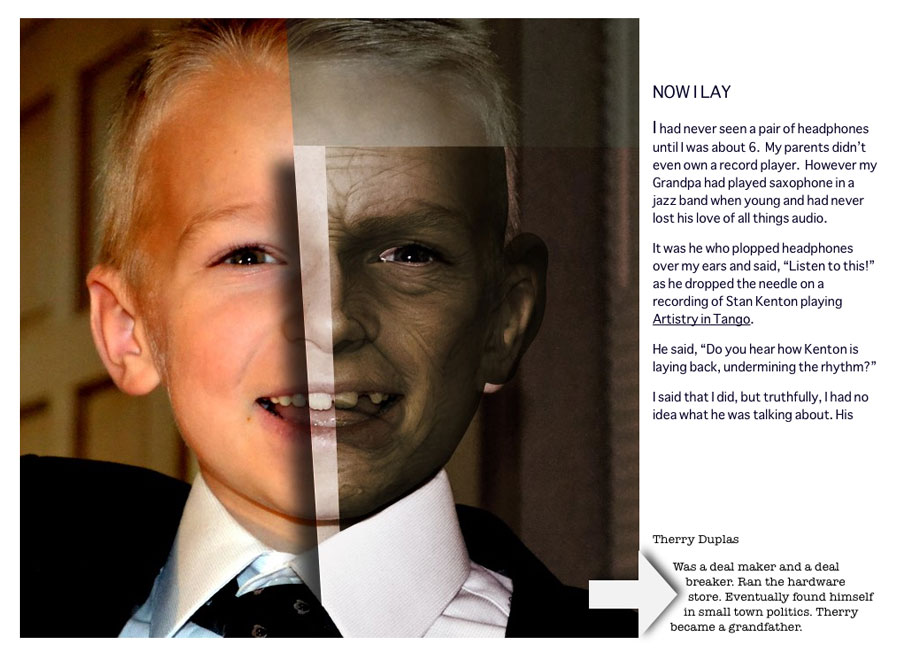

Grandpa’s favorite private time activity was caring for his collection of jazz 78s. Grandpa would pull me away from playing with Tommy to hear a record he had recently bought. Even though only a kid, I seemed to be the only other human in the family interested in listening to the records. Tommy stayed close by and watched us with no sense of curiosity. I committed to music because of Grandpa. He was my inspiration.

Additionally, Grandpa could count on me to listen to his adventures as a youth. His best story was how he survived the Great Storm of 1900. Grandpa was 9 years old and living near Galveston, Texas when a hurricane totally submerged the island, causing thousands of people to drown. I have since read about the storm and it was horrific. I asked Grandpa how he managed to survive. In 1900 there was no way of knowing a hurricane was bearing down on the small island. When the lightning started, he and his buddies walked to the beach where they could better see the sky. A beach is not the best place to be in a hurricane or a lighting storm as far as that goes. Once the waves became huge, rolling onto the land, they ran to a nearby lighthouse. He said that a number of people were in the lighthouse and all of them survived. They were lucky. Eight thousand other island dwellers did not.

I became so enamored with this tale that, as an adult, Roman and I made a kind of pilgrimage to Galveston to see the island I had imagined so many times. I hoped to find the lighthouse. After all, had Grandpa died in the storm, neither my mom nor I would exist. As it turned out there was only one lighthouse in 1900 and it was still standing though closed to the public. I stood near it imagining Grandpa and the other kids laughing as they ran to safety, not realizing how deadly the storm would turn out to be.

Grandpa survived the hurricane, but Grandpa could not survive life.

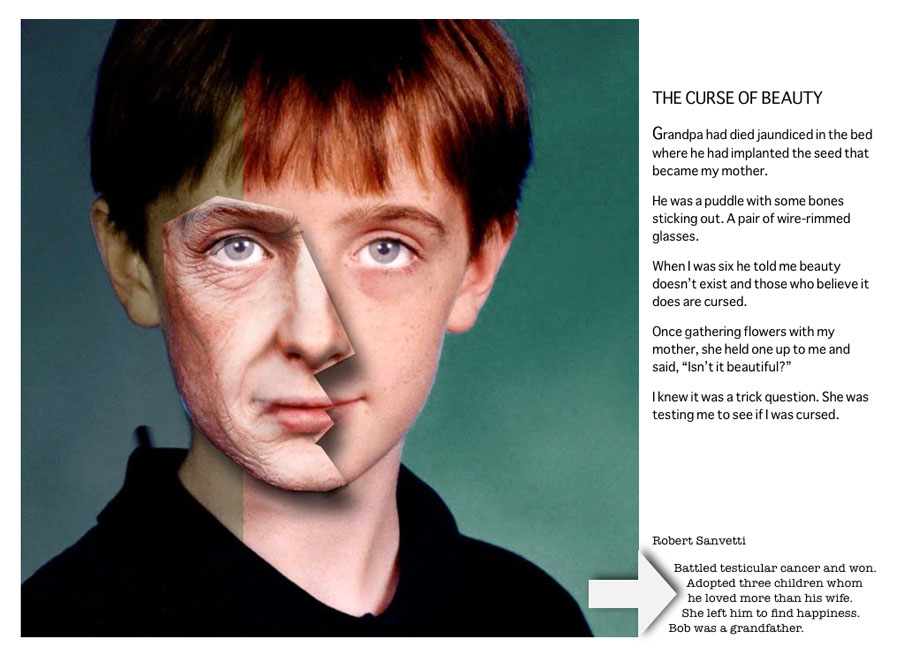

The old man died of cancer at 84. Cigars. He was allowed to die at home. My mother and I walked to the side of his bed to say goodbye. An odor of sickness almost made me gag. He was yellow and sweat rolled from his forehead. He looked at me with eyes that seemed too small for his head. Grandpa touched me with his bony hand and mumbled something that I could not hear. From watching movies I knew I should lean over to grasp his final words. But I didn’t do that. Grandpa and I developed angry differences as adults and I thought the words could be hurtful. So instead I patted his shoulder gently like I might a dog and whispered, “I love you too.”

My mind was conflicted over refusing to hear what he actually had to say. Death is so permanent yet it cleanses with its finality. I was still mulling my relationship with the man when Tommy came in. I had not seen him in years but his face was unchanged, appearing youthful and vacant. He looked to Grandma and asked what was wrong with Grandpa. She looked back and told him that Grandpa was preparing to take a long trip to Heaven. Tommy grinned in the direction of Grandma seeking confirmation that going to Heaven was a good thing. A very tired Grandma told him it was a good thing, a very good thing. While everyone in the room other than me believed that going to Heaven was a good thing, Tommy was the only one to practice what the others preached. He burst into a happy laugh. Tommy never laughed. Tommy clapped his hands and started to bob a little as he had seen others do on preaching TV shows. A few of us snickered at first but soon others were joining Tommy, clapping and bouncing. Even cynical me jumped in upon feeling that innocent joy overwhelm any sadness.

I suppose Tommy’s entire life built to that moment. His existence suddenly had purpose as he became our leader showing us the way back to being alive. Tommy had won acceptance as a full-fledged member of the human race for the first time in his life, if only for a moment. We took turns embracing him. It never occurred to me that he had the capacity for being happy.

Grandpa gave up the fight. We gathered around to watch life drip from him. The question of the chicken or the egg never occurred to Grandpa. He was egocentric enough to believe that he came first, and his wife and daughters were less important than the men. The women did not cry from the loss, they cried because it was finally over. The men did not cry at all. The women understand that they will have to stand next to more than one man dying. It is what they do. Someone mumbled that he was a good man. He wasn’t a good man, he was a perfectly adequate man. He did what was needed, deposited his sperm, then got out of the way.

After the burial, I never saw Tommy again. He joined Grandpa in Heaven a year later. Mother said he had dropsy.

Grandma, on the other hand, lived many more years. She saw daughters give birth to daughters who gave birth to yet more daughters. At 90 she married a man she met in the old folks home. He was fat and couldn’t reach his feet so she had to trim his toenails.

Neither paused to consider roosters. Roosters and the vast majority of male animals have always been regarded primarily as accessories to the process of the continuation of the species. I have no problem with that. Women producing daughters with the ultimate purpose of those daughters making more daughters seems like a sensible system which allows for a beautiful tradition of photographs with four or five generations of mothers and daughters.

Men were not overlooked. It’s just that nature never intended them to be in the photos to start with. Especially affected were the older men, the grandfathers, the great-grandfathers. They tended to become primarily decorative additions to overstuffed chairs.

This was true for my grandfather. And in time, so it will be with me.

When my mom was young, my grandfather provided for her and the rest of the family in the manner that was expected of men during the Great Depression. He had his personal interests; his work, music, reading, smoking cigars, but satisfaction came from providing for the family. Once mother married, replacing him with a husband, his center became blurred. She was the final chick leaving the coop and he suddenly found himself with little distraction other than a wife he had not noticed in many years.

While my mother was the last to leave home, she was not the youngest child. She had a younger brother, Tommy, who had suffered a difficult birth. I don’t know what went wrong, medicine was not very sophisticated in small towns in Arkansas a hundred years ago. The younger uncle had the mind of a child. He was kept at home, never going to school, church, or anywhere that might cause embarrassment or require explanations. When I was young and visited the grandparents, Tommy and I played together, we both loved to draw. While I would copy characters from comic books, he mainly copied cigarette advertisements from magazines. He liked to draw women smoking. I thought he was a terrible artist back then. I might have a different opinion now.

Grandpa’s favorite private time activity was caring for his collection of jazz 78s. Grandpa would pull me away from playing with Tommy to hear a record he had recently bought. Even though only a kid, I seemed to be the only other human in the family interested in listening to the records. Tommy stayed close by and watched us with no sense of curiosity. I committed to music because of Grandpa. He was my inspiration.

Additionally, Grandpa could count on me to listen to his adventures as a youth. His best story was how he survived the Great Storm of 1900. Grandpa was 9 years old and living near Galveston, Texas when a hurricane totally submerged the island, causing thousands of people to drown. I have since read about the storm and it was horrific. I asked Grandpa how he managed to survive. In 1900 there was no way of knowing a hurricane was bearing down on the small island. When the lightning started, he and his buddies walked to the beach where they could better see the sky. A beach is not the best place to be in a hurricane or a lighting storm as far as that goes. Once the waves became huge, rolling onto the land, they ran to a nearby lighthouse. He said that a number of people were in the lighthouse and all of them survived. They were lucky. Eight thousand other island dwellers did not.

I became so enamored with this tale that, as an adult, Roman and I made a kind of pilgrimage to Galveston to see the island I had imagined so many times. I hoped to find the lighthouse. After all, had Grandpa died in the storm, neither my mom nor I would exist. As it turned out there was only one lighthouse in 1900 and it was still standing though closed to the public. I stood near it imagining Grandpa and the other kids laughing as they ran to safety, not realizing how deadly the storm would turn out to be.

Grandpa survived the hurricane, but Grandpa could not survive life.

The old man died of cancer at 84. Cigars. He was allowed to die at home. My mother and I walked to the side of his bed to say goodbye. An odor of sickness almost made me gag. He was yellow and sweat rolled from his forehead. He looked at me with eyes that seemed too small for his head. Grandpa touched me with his bony hand and mumbled something that I could not hear. From watching movies I knew I should lean over to grasp his final words. But I didn’t do that. Grandpa and I developed angry differences as adults and I thought the words could be hurtful. So instead I patted his shoulder gently like I might a dog and whispered, “I love you too.”

My mind was conflicted over refusing to hear what he actually had to say. Death is so permanent yet it cleanses with its finality. I was still mulling my relationship with the man when Tommy came in. I had not seen him in years but his face was unchanged, appearing youthful and vacant. He looked to Grandma and asked what was wrong with Grandpa. She looked back and told him that Grandpa was preparing to take a long trip to Heaven. Tommy grinned in the direction of Grandma seeking confirmation that going to Heaven was a good thing. A very tired Grandma told him it was a good thing, a very good thing. While everyone in the room other than me believed that going to Heaven was a good thing, Tommy was the only one to practice what the others preached. He burst into a happy laugh. Tommy never laughed. Tommy clapped his hands and started to bob a little as he had seen others do on preaching TV shows. A few of us snickered at first but soon others were joining Tommy, clapping and bouncing. Even cynical me jumped in upon feeling that innocent joy overwhelm any sadness.

I suppose Tommy’s entire life built to that moment. His existence suddenly had purpose as he became our leader showing us the way back to being alive. Tommy had won acceptance as a full-fledged member of the human race for the first time in his life, if only for a moment. We took turns embracing him. It never occurred to me that he had the capacity for being happy.

Grandpa gave up the fight. We gathered around to watch life drip from him. The question of the chicken or the egg never occurred to Grandpa. He was egocentric enough to believe that he came first, and his wife and daughters were less important than the men. The women did not cry from the loss, they cried because it was finally over. The men did not cry at all. The women understand that they will have to stand next to more than one man dying. It is what they do. Someone mumbled that he was a good man. He wasn’t a good man, he was a perfectly adequate man. He did what was needed, deposited his sperm, then got out of the way.

After the burial, I never saw Tommy again. He joined Grandpa in Heaven a year later. Mother said he had dropsy.

Grandma, on the other hand, lived many more years. She saw daughters give birth to daughters who gave birth to yet more daughters. At 90 she married a man she met in the old folks home. He was fat and couldn’t reach his feet so she had to trim his toenails.